The Big Windermere Survey: Citizen science exposes ecological strain on England’s largest lake

20 October, 2025

A community-powered survey reveals nutrient enrichment, bacterial contamination, and climate-linked vulnerabilities in Windermere.

Freshwater ecosystems are among the most threatened on the planet, yet they remain under-monitored compared with terrestrial and marine environments. In the UK, Windermere – England’s largest natural lake – is both a cherished cultural landmark and a sentinel of ecological change.

Over the last three years, the Big Windermere Survey (BWS), has provided the most comprehensive dataset yet assembled for an English lake, highlighting the potential of citizen science to generate robust, policy-relevant evidence.

About the Big Windermere Survey

BWS is an innovative and impactful citizen science project first developed in 2022 through collaboration between the FBA and Lancaster University to assess the environmental health of Windermere, in response to community concerns and gaps in traditional water quality monitoring.

Launched in June 2022, the BWS engaged more than 350 trained volunteers in a coordinated programme of field sampling, supported by professional laboratory analysis. Over 2.5 years, from June 2022 to November 2024, volunteers collected water samples at more than 100 sites across the Leven catchment, including rivers and smaller waterbodies, and both near-shore and open-water sites in both north and south basins in Windermere. The scale of this participatory effort has revealed spatial and temporal patterns of nutrient enrichment and bacterial hotspots that place the lake under significant ecological stress.

“The Big Windermere Survey is a citizen science initiative, and citizen science is basically bringing together concerned communities to gather data and evidence to understand better the issues that they might be concerned about, particularly on places like Windermere … we’ve brought 350 volunteers together and collectively over the last two and a half years on 120 sites, once every season, we’ve gone out and we’ve sampled water quality.”

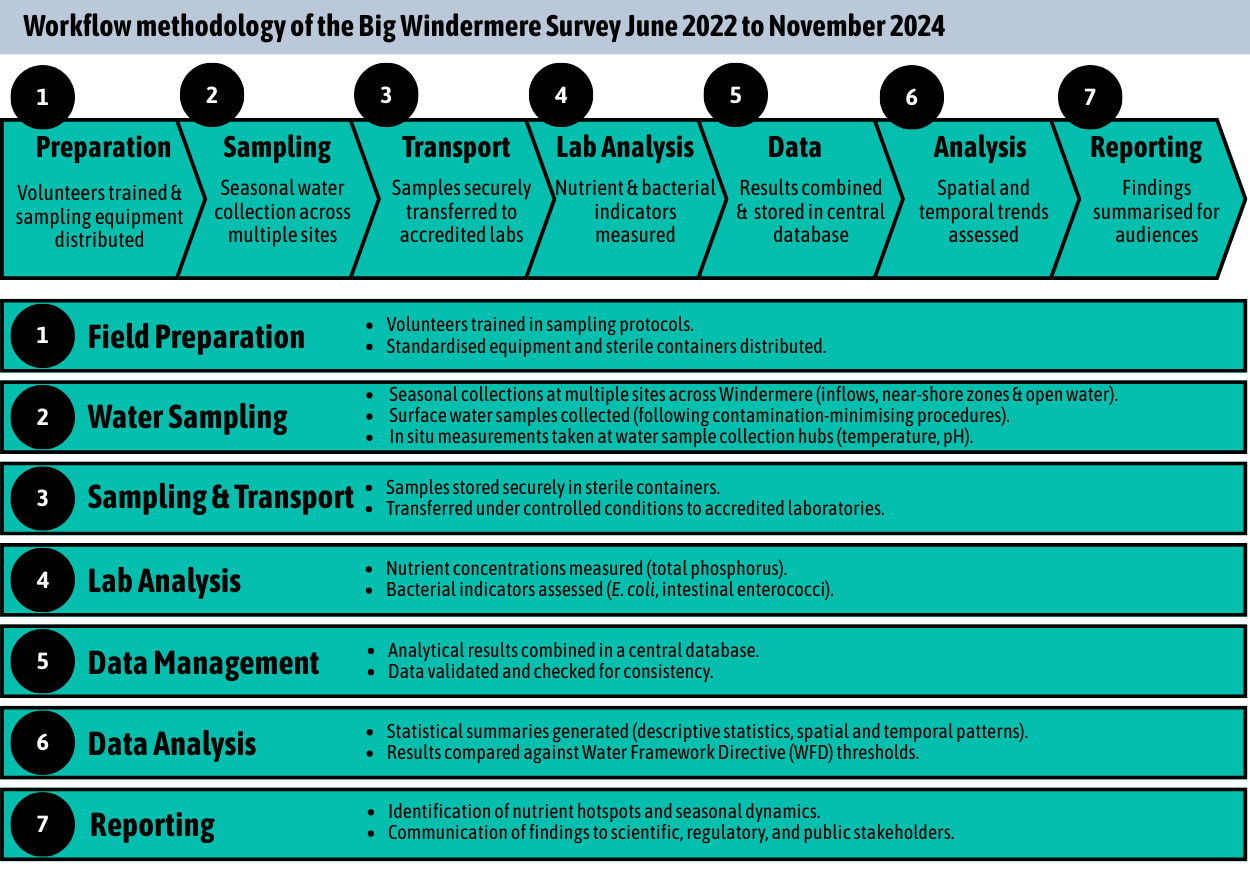

BWS Methodology: Blending citizen science with professional rigour

The BWS was designed as a hybrid monitoring system. Volunteers followed stringent protocols for surface water collection, reducing contamination risks and ensuring comparability across sites. Handheld instruments were used to measure temperature, pH, and conductivity at locally situated hubs, while samples were transported under controlled conditions to accredited laboratories for further analysis.

Analyses focused on nutrient chemistry and bacterial indicators (Escherichia coli and intestinal enterococci).

The BWS methodology demonstrates that citizen-led sampling coupled with professional laboratory analysis, can provide reliable datasets. Such a model is increasingly relevant in an era of resource constraints and rising demands for environmental monitoring.

Some of the Big Windermere Survey citizen scientists collecting water samples from Windermere in the Lake District.

Graphic showing the seven stage methodology of the Big Windermere Survey.

A template for freshwater monitoring

The BWS exemplifies the potential of citizen science to fill monitoring gaps. By mobilising volunteers using standardised protocols and coupling their efforts with laboratory analyses, the project achieved a breadth and resolution that would be otherwise financially prohibitive and logistically untenable.

This model is transferable. Many lakes across Europe and beyond face similar pressures yet lack the data to guide management. Replicating the Windermere approach can supply policymakers with the robust evidence they need.

Perhaps most significantly, the BWS demonstrated that structured citizen science, when integrated with professional analysis, can produce scientifically robust data at a scale that would otherwise be financially prohibitive. This provides a replicable model for freshwater monitoring globally.

Findings from the BWS: Signals of stress

The results are stark. Spatial patterns revealed how phosphorus concentrations vary around the lake and hotspots of high concentrations of both phosphorus and bacteria were identified, including at many sites that have never previously been analysed for water quality. The results highlight key locations at with elevated phosphorus concentrations, with concentrations peaking in summer.

Bacterial tests detected Escherichia coli (E. coli) and intestinal enterococci concentrations above bathing water safety thresholds. Likely sources include combined sewer overflows, septic tank leakage, and inputs from agricultural runoff and wildfowl faeces.

The survey also revealed that concentrations of E. coli and IE bacteria were highest in the summer months, at times when Windermere is especially popular for activities such as bathing and water sports. Based on the report data, in summer concentrations of bacteria in the Northwest, Northeast and Southwest areas of the lake in summer were only consistent with standards for ‘Poor’ bathing water quality.

Find out more and read the two-year Big Windermere Survey report.

The Big Windermere Survey message is unambiguous: Windermere is under ecological strain. Without decisive intervention to curb nutrient and bacterial pollution, and to prepare for climate-driven extremes, the lake will remain in its degraded condition.

But there is also hope. The BWS shows that citizen science can complement professional monitoring to deliver actionable data at an unprecedented scale. For freshwater ecosystems under threat, this approach is not just desirable – it is essential.

“Windermere, like many water bodies across the UK, faces a number of pressures, most of which are human-related. These include wastewater inputs from mains sewage, water companies, and private systems, as well as agricultural runoff, urban runoff, and pollution from roads. Each of these pressures affects the water in different ways. For example, bacteria can impact the safety of the water for both people and animals, while high levels of phosphorus can lead to eutrophication, a process that can lead to ecosystem collapse. To protect and restore the lake, we need to reduce these pressures and their inputs. By moving towards a more naturally functioning lake, everything else within the ecosystem should start to recover and thrive.”

Recommendations for action

Based on its findings, the BWS team has issued a multi-pronged set of recommendations for key next steps on tackling nutrient enrichment and high bacterial loading in Windermere and how BWS can underpin these activities and help target action.

Graphic showing four key next steps on tackling nutrient enrichment and high bacterial loading in Windermere and how BWS can underpin these activities and help target action.

1. Address hotspots of poor water quality

The priority must be to identify and address causes of high nutrient and bacterial concentrations at key hotspots identified by the BWS. Some are long-standing issues requiring urgent action. While some hotspots, like Mill Beck and Waterhead, are near urban areas connected to mains sewerage (the infrastructure through which sewage flows), most are not. This highlights the need to investigate alternative pollution sources, including private wastewater systems, agricultural runoff, and wildfowl faeces. The BWS team is keen to collaborate with catchment partners to address these complex challenges.

2. Invest in enforcing regulation, investigation work and infrastructure

Urgent investment is needed both to ensure that all wastewater infrastructure (private and water company) is fit for purpose and adequately monitored. Equally, regulatory capacity must be strengthened to investigate and tackle pollution risks swiftly and rigorously.

3. Increase monitoring and reporting in waters used for recreation

We urge the Environment Agency to utilise the bacterial data generated by the BWS. We recommend consideration of key issues such as the number and distribution of monitoring locations at designated bathing waters on Windermere, and expanding the seasonal timing of bathing water quality assessments. There is also an urgent need for clearer, more frequent, and publicly accessible communication on local water quality. We believe that Windermere could become an exemplar case study, demonstrating how collaborative, holistic action can effectively address water quality pressures within a catchment that is both iconic and under substantial pressure from human activity and climate change.

4. Build a robust evidence base – funding the Big Windermere Survey

Data from the BWS, alongside other key datasets, provides evidence to focus action and deliver faster benefits for nature and people. The last BWS took place in November 2024 and has not continued due to a lack of financial support. The BWS showcases how citizen scientists, working with academic partners, generate robust data and meaningful community engagement. Key actors in the Windermere catchment should unite to fund its continuation and guide future strategies to improve water quality.

“So there’s two reasons really that I got fundamentally involved in the Big Windermere Survey at its outset in helping to design it. The first one was to engage members of the community in understanding and actually helping to monitor water quality in Windermere and that’s been a really valuable part of the project and I hope that that continues into the future, both at Windermere but also in other freshwaters within the area ... The second thing I really hope for is that we can work with partners in the catchment to drive changes that lead to real improvements in Windermere’s water quality. Clearly the Big Windermere Survey has created this unique evidence base telling us about water quality, the challenge now is to work with partners with the remit to enact change in the catchment so that we can protect Windermere in the future.”

Concluding comments

The Big Windermere Survey marks a pivotal step in freshwater science, showing how large-scale, volunteer-driven monitoring can uncover ecological stressors with rigour sufficient to inform policy. Windermere’s condition, as revealed by the BWS two-year report, is emblematic of broader freshwater challenges worldwide – where nutrient pollution, bacterial contamination, and climate variability intersect.

The findings highlight both the fragility of lake ecosystems and the power of collaborative science. By blending citizen participation with professional validation, the BWS demonstrates a scalable approach to environmental monitoring at a time when society urgently needs high-resolution data. The future of Windermere, and lakes like it, will depend not only on continued observation but also on decisive action to curb pollution and adapt to a changing climate.

Heartfelt thank you to all the dedicated volunteer citizen scientists who took part in the Big Windermere Survey!

Interested in finding out more?

Find out more about the Big Windermere Survey and download the two-year report.

For further details of bacterial spatial patterns with supporting interactive maps, and phosphorus spatial patterns with supporting interactive maps, view the Big Windermere Survey Report Maps.

Read more about the importance of citizen science to help assess the environmental health of Windermere.