Survival of young freshwater pearl mussels: insights from in-situ experiments in two northern rivers

16 December, 2025

Samantha Bonny (1)*, Louise Lavictoire (1), Toby Panter (2), Jodie Warren (1) & Ben King (1).

(1) Freshwater Biological Association (FBA); *SBonny@fba.org.uk; (2) North York Moors National Park Authority.

Samantha is the FBA’s River Kent Project Officer and also works on the freshwater pearl mussel breeding programme. Here, Samantha and collaborators report on trials they ran to assess whether the rivers Esk and Kent would be suitable for population reinforcements of juvenile mussels, thus supporting future populations of this endangered species.

Edited by Rachel Stubbington, Nottingham Trent University

Rachel is both a Fellow of the Freshwater Biological Association and long-standing Editor of FBA articles. If you would like to submit an article for consideration for publication, please contact Rachel at: rachel.stubbington@ntu.ac.uk

Introduction

The last century has seen dramatic declines in European populations of freshwater pearl mussels (FPM, Margaritifera margaritifera) due to overharvesting, river modification and pollution (Cosgrove et al. 2016). Now classified as ‘critically endangered’ in Europe, their disappearance from rivers is reducing both biodiversity and water quality. In response, efforts to conserve this bivalve include water quality improvements and captive breeding programmes, such as the FBA’s Species Recovery Programme (Geist 2010).

In September 2025, the FBA concluded a year-long mussel ‘silo trial’ which involved two parallel studies. One, in the River Kent, Cumbria, is part of the LIFE R4ever Kent project and is in a catchment with just three known adult FPM; the second, in the River Esk, Yorkshire, is through the Esk and Coastal Streams Catchment Partnership and also has a small, aging, non-recruiting FPM population. Both studies investigated whether water quality and food availability in the rivers could support juvenile mussel growth and survival, with the aim of determining whether juveniles should be reinforced in these rivers. The FBA and the North York Moors National Park Authority carried out the River Kent and Esk trials, respectively.

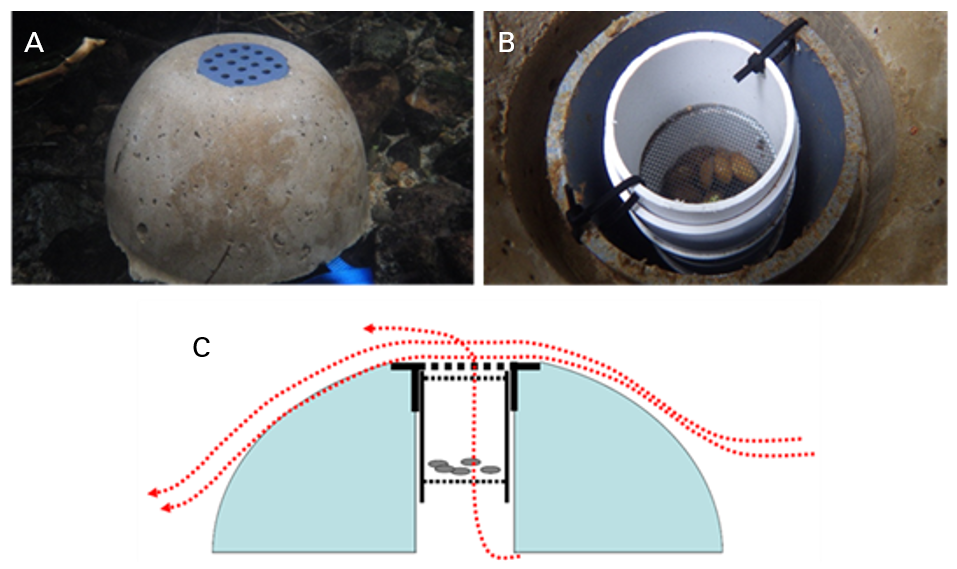

Mussel silos are concrete domes which act as short-term holding systems to house juveniles in situ. Each silo has a chamber that can hold a secure cup of mussels (Figure 1). The structures work on Bernoulli’s principle: water moves faster over the top of the silo, drawing water up from underneath which passes through the cup containing the mussels, supplying them with food and oxygen. Developed by researchers including Chris Barnhart (Missouri State University), the FBA has successfully used silos to investigate site suitability and prioritise release sites in the River Irt, Cumbria (Lavictoire & West 2020).

Figure 1. Mussel silos (A) from above; (B) below with a chamber containing mussels in a cup; and (C) in cross section. From Barnhart et al. (2007) and Lavictoire & West (2020).

Methods

At three cobble- and pebble-dominated sites in both rivers, five silos were placed on the riverbed (Figure 2). The River Kent sites were chosen based on their potential suitability as mussel reinforcement sites – 4,000 juvenile mussels are intended for release into the Kent before September 2028, as part of the R4ever Kent project. Five silos were also maintained in a tank at the FBA’s Species Recovery Centre (SRC) to act as a control group.

Figure 2. The three sites in the River Esk (top) and River Kent (bottom).

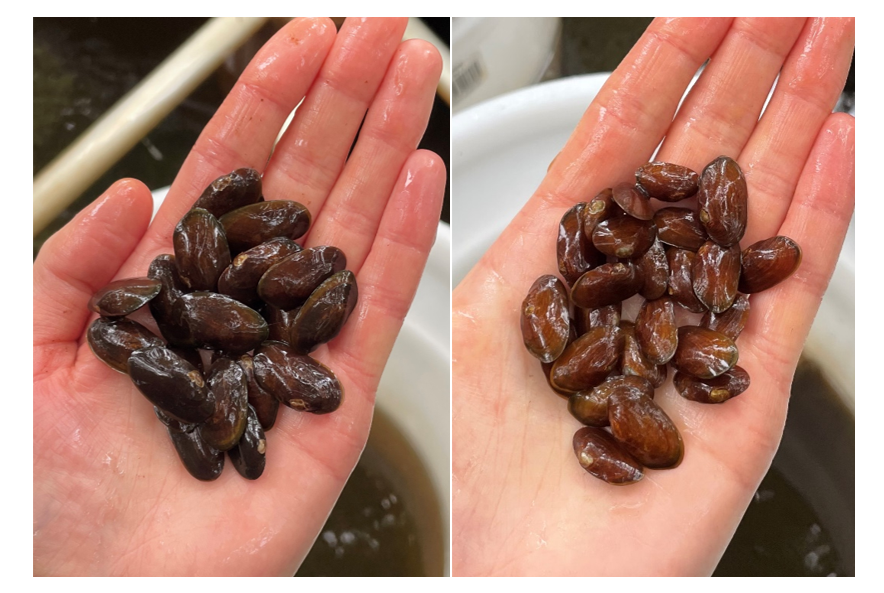

The trial mussels were from the River Irt population’s 2019 cohort, which has a large, propagated population at the SRC. Mussel length was measured and 30 individuals of 12–15 mm were placed into each cup (Figure 3); this was then closed and secured inside a silo.

Figure 3. (A) Propagated mussels used in the silo trials, and (B) a cup containing 30 juvenile mussels.

The silos were monitored monthly by removing and opening the cups and counting any dead mussels, which were identified by a permanently open shell. We also made observations including shell colour (a potential sign of nutrient inputs), silt (which blocked flow through the silos) and byssal threads (which suggest mussel exposure to turbulence).

At the end of the trial, mussels were remeasured then returned to SRC populations. We used a non-parametric ANOVA-type test with pairwise comparisons to compare growth rates among the two rivers and the control.

Results

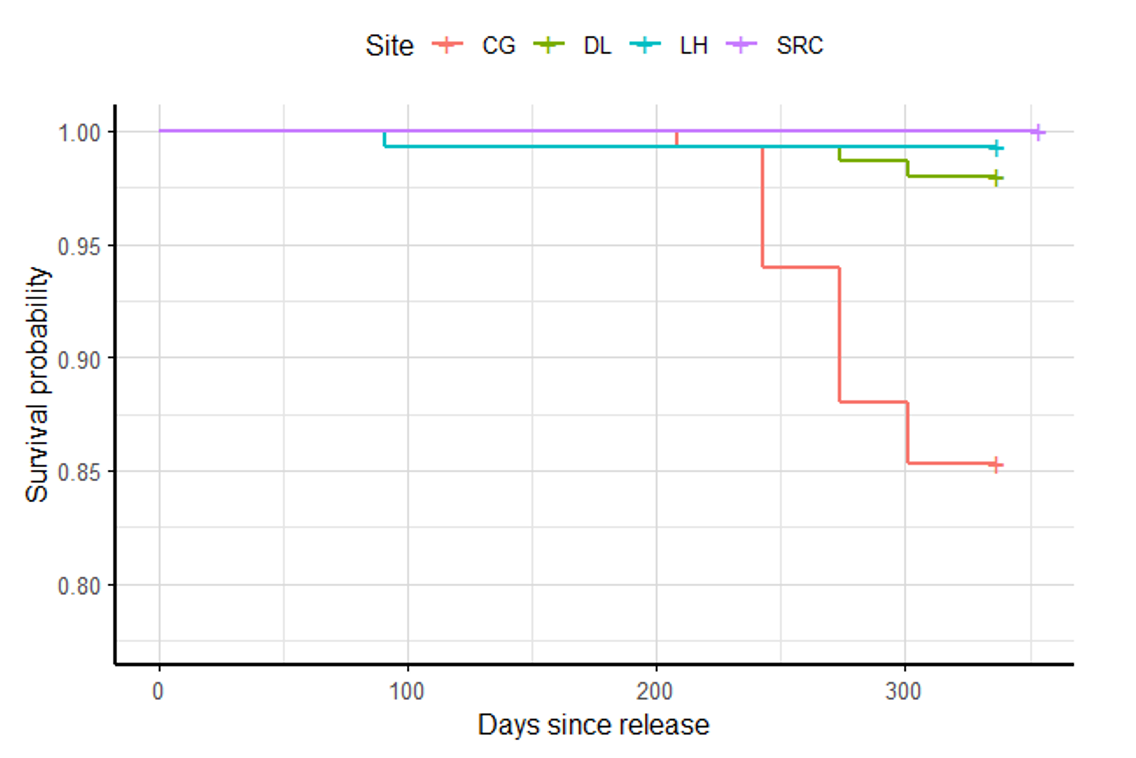

The control group experienced 100% survival. In the River Kent, survival was also 100% at two sites, demonstrating that the mussels had acquired enough food from the water column and tolerated the river water quality. However, the third site was discounted as a potential release site after high flows washed three silos far downstream, indicating that the reach is too high-energy for juvenile mussels to survive. On the River Esk, mortality was 0.7–14.7% at all sites (Figure 4). The largest mortality event, at site CG, likely reflected low flows and associated fine sediment deposition during drought in summer 2025, which clogged silos and reduced the oxygen supply to the mussels.

Figure 4. Survivorship curves for mussels at three Esk sites and the SRC control group.

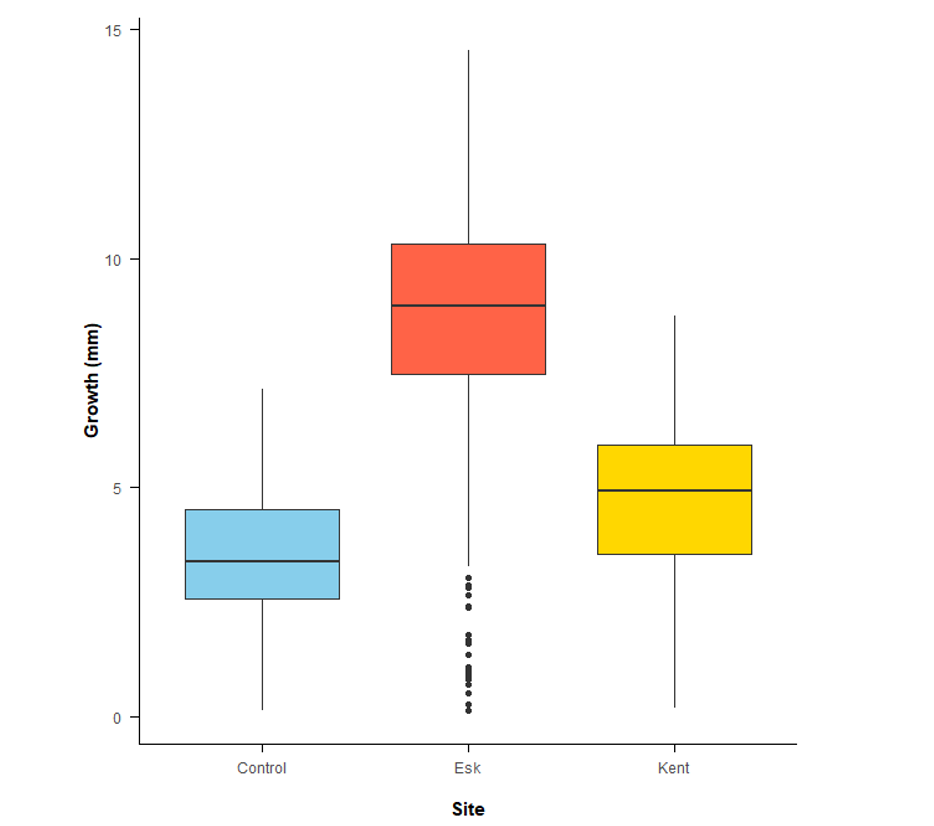

Mean growth over the 1-year study period (Figure 5) was higher for Esk (8.69 ± 2.48 mm) compared to Kent (4.74 ± 1.74 mm) and control (3.48 ± 1.37 mm) populations, and also higher for Kent than control populations (pairwise tests, all p <0.001).

Figure 5. Mussel growth in the Rivers Esk and Kent and the control group.

Shell colour in the Esk mussels was substantially darker than the control mussels (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Freshwater pearl mussel shell colour comparison between the River Esk (left), and Kent silo mussels (right).

Discussion

The silo trials enabled investigation of in-situ FPM survival. The findings suggest two sites in the River Kent as suitable for juvenile mussel releases based on water quality and food availability, which will influence the location of releases in the R4ever Kent Project in 2026–2028.

Higher growth rates and higher mortality at all Esk sites indicate we need to better understand the drivers affecting survival before reinforcements take place. This aligns with observations from concurrent FBA research that habitat conditions in the River Esk are not suitable for juvenile mussel releases (Bonny & Lavictoire 2025).

The greater growth of the Esk mussels compared to the control mussels likely reflects higher nutrient availability (Bartsch et al. 2017). Nutrient loading, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen from farming, increases algal productivity, food availability and thus mussel growth rates (Valdovinos & Pedreros 2007). Nutrient inputs were likely higher in the Esk than the Kent because Esk catchment land uses are primarily intensive arable land and moorland (Environment Agency 2010), with more sewage treatment works, whilst the Kent catchment is dominated by low-intensity livestock grazing (Environment Agency 2025). FPM are slow-growing and long-lived, and accelerated growth rates could reduce their number of breeding cycles and longevity, with implications for population dynamics, recruitment and health (Haag & Rypel 2011). Moreover, nutrient inputs can be associated with decreased dissolved oxygen concentrations and increased ammonium concentrations, both of which can negatively affect mussel growth and long-term survival (Newton & Bartsch 2007).

Conclusion

Mussel silos are a simple and effective method to assess how juvenile mussels fair under current river conditions, informing potential release efforts. These trials offered support for two chosen mussel reinforcement sites in the River Kent and stressed the need for river condition and water quality improvements in the River Esk, to conserve this vulnerable population.

References

Barnhart, M.C. et al. 2007. Mussel silos: Bernoulli flow devices for caging juvenile mussels in rivers. In Fifth biennial symposium of the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Bartsch, M.R. et al. 2017. Effects of food resources on the fatty acid composition, growth and survival of freshwater mussels. PLoS One 12: e0173419. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173419

Bonny, S. & Lavictoire, L. 2025. Freshwater pearl mussel habitat mapping in the River Esk, Yorkshire. Unpublished report to Yorkshire Water. FBA, UK.

Cosgrove, P. et al. 2016. The status of the freshwater pearl mussel Margaritifera margaritifera in Scotland: extent of change since 1990s, threats and managementimplications. Biodiversity and Conservation 25: 2093–2112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1180-0

Environment Agency 2010. Esk and Coastal Streams Catchment Flood Management Plan. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7c7f19e5274a2674eab0b4/Esk_and_Coastal_Streams_Catchment_Flood_Management_Plans.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Environment Agency 2025. Kent Operational Catchment. https://environment.data.gov.uk/catchment-planning/OperationalCatchment/3243

Geist, J. 2010. Strategies for the conservation of endangered freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera L.): a synthesis of conservation genetics and ecology. Hydrobiologia 644: 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-010-0190-2

Haag, W.R. & Rypel, A. 2011. Growth and longevity in freshwater mussels: evolutionary and conservation implications. Biological Reviews 86: 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00146.x

Lavictoire, L. & West, C. 2020. A European mussel silo (based upon Chris Barhnart’s silo design of 2020). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.23113.36962

Newton, T.J. & Bartsch, M.R. 2007. Lethal and sublethal effects of ammonia to juvenile Lampsilis mussels (Unionidae) in sediment and water‐only exposures. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 26: 2057–2065. https://doi.org/10.1897/06-245R.1

Valdovinos, C. & Pedreros, P. 2007. Geographic variations in shell growth rates of the mussel Diplodon chilensis from temperate lakes of Chile: Implications for biodiversity conservation. Limnologica 37: 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.limno.2006.08.007

Copyright statement

All figures are © the authors.

Further FBA reading

The Freshwater Biological Association publishes a wide range of books and offers a number of courses throughout the year. Check out our shop here.

Get involved

Our scientific research builds a community of action, bringing people and organisations together to deliver the urgent action needed to protect freshwaters. Join us in protecting freshwater environments now and for the future.