A legacy of lead in a stormy future: the case of Ullswater in the English Lake District

16 January, 2026

By D.G. George, dgg.abercuch@gmail.com.

Glen George is an Honorary Research Fellow with the FBA and holds visiting Professorships at Aberystwyth University and University College London. In this article, using the 1927 Greenside Mine disaster at Ullswater as a case study, he explains why the ongoing increase in the intensity of extreme weather events could lead to the re-emergence of water quality problems that were thought to have been resolved.

Edited by Rachel Stubbington, Nottingham Trent University

Rachel is both a Fellow of the Freshwater Biological Association and long-standing Editor of FBA articles. If you would like to submit an article for consideration for publication, please contact Rachel at: rachel.stubbington@ntu.ac.uk

Introduction

Today, England’s Lake District National Park is regarded as a rural idyll, but in the 18th and 19th centuries many remote valleys were industrial sites. Most were associated with the extractive industries, with copper being mined at Coniston and lead near Ullswater, England’s second largest lake. The environmental impacts of these past activities have declined over subsequent decades, but some have had long-term—and ongoing—consequences.

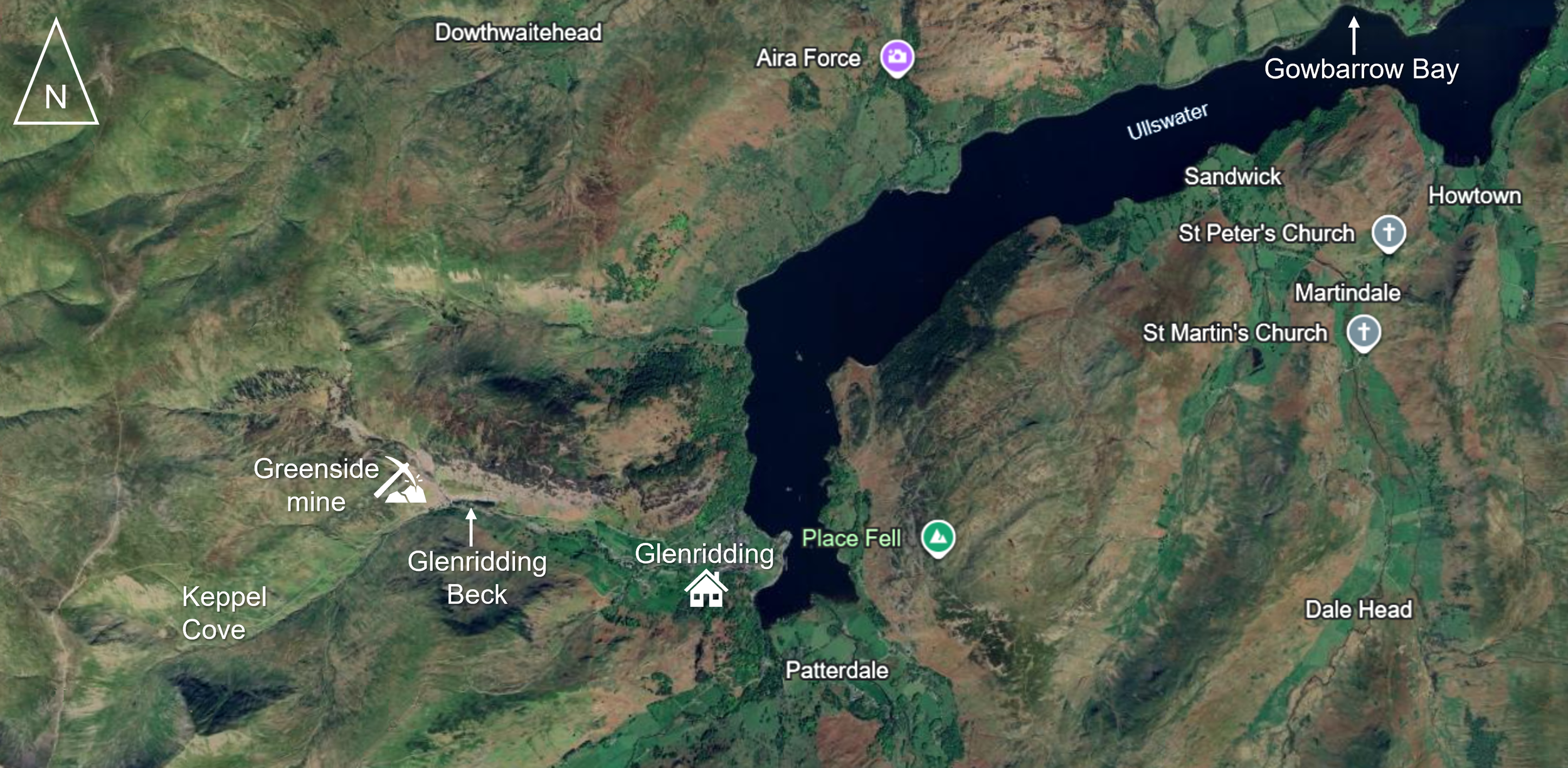

Figure 1. Ullswater lake, illustrating the southwestern area impacted by the Greenside Mine collapse. Map reproduced from Google Earth.

A striking example is the lead pollution that followed the collapse of a dam at the Greenside Mine above Ullswater (Figures 1 and 2) in 1927. At the time, Greenside was the largest galena (a mineral form of lead) mine in Britain, and the effects of the lead released still affect the lake. Glenridding Beck, the stream that bore the brunt of the discharge from the collapse flows through the village of Glenridding before entering Ullswater at its southern end. The disaster is thought to have had a major effect on the lake’s aquatic plant (macrophyte) communities, but these effects were not studied for several decades.

Figure 2. The Greenside Mine site, showing its current use as a residential field study centre.

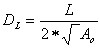

The early study of macrophyte communities in Ullswater

In 1921, Pearsall, one of the founders of the FBA, published an important study on the classification of English Lakes. This showed that they formed a continuum from lakes with very low nutrient concentrations, like Wastwater, to those that were very productive, like Esthwaite Water. Collections made at the time showed that Ullswater supported a thriving community of submerged and emergent macrophytes. The productivity of this community reflected the balance of three critical factors: 1. the trophic status of the lake, as measured by winter concentrations of dissolved reactive phosphorus; 2. the transparency of the water, as measured using a Secchi disc; and 3. the morphometry of the lake, as described by a shoreline development index. Figure 3 shows the relationship between these attributes for the first (i.e. least productive) seven lakes in the Pearsall series.

The phosphorus and Secchi disk measurements were acquired by the FBA in the 1970s, when all the lakes were sampled four times a year. The morphometric index is based on measurements taken from a 1:25,000-scale map and is the ratio of the shoreline length to the length of the circumference of a circle with an area equal to that of the lake:

Ratios close to one represent lakes with few sheltered bays whereas higher ratios describe those with a more irregular shoreline. These analyses show that Ullswater occupies a ‘Goldilocks’ position in the series by being reasonably productive, not too dark (Figure 3a), and with an irregular shoreline with some sheltered bays in which plants can take root (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. The relationship between winter concentrations of dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP) and (a) the transparency of the water and (b) the shoreline development index (Shore D), for the first seven lakes in the Pearsall series, including Ullswater (Ulls).

When Pearsall sampled the lake between 1913 and 1920, he recorded seven species of emergent and 10 species of submerged plants—but that was seven years before the Greenside Mine disaster. Ullswater’s condition in the 1930s and 1940s is little known, but a report published in the Guardian in 1939 implied that any swans that colonised the lake were killed by lead poisoning (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A cutting from the UK newspaper the Guardian in 1939.

The Greenside Mine disaster

The new mine at Greenside opened in 1825 and used large quantities of lake water to power its machinery and wash the ore. In the 1890s, the decision was taken to build an earth dam across Keppel Cove, an armchair-shaped hollow in the hills above Ullswater (Figure 1), to power the mine. Around this time, hydropower replaced the old water wheel and the mine was one of the first in Britain to use electricity. On 4th November 1927, the engineers closed the sluice gates in the dam to accumulate a good supply of water. Later that day, a storm struck the area, the water level rose and waves driven by the strong winds destroyed the top of the dam. The result was a tidal wave that swept down Glenridding Beck to flood many of the shops and houses along its bank (Figure 5). The associated slurry was initially deposited in the Glenridding basin, but was soon resuspended and transported north in Ullswater by the prevailing winds and associated currents.

Figure 5. Cleaning up outside the Refreshment Rooms in 1927. From the Patterdale Past website.

The disaster’s ecological impact on the lake

After the disaster, the first comprehensive measurements of lead in the lake showed that concentrations in the water were slightly elevated, but much higher in the sediments and submerged plants (Mackereth 1965). More detailed studies of Ullswater by Welsh and Denny (1980) detected high lead concentrations in sediments as far north as Gowbarrow Bay (Figure 1). They showed that the highest lead concentrations were then found in sediments 10 cm below the mud surface and in the roots of aquatic plants. Some plants contained much higher concentrations of lead than others which implied that uptake was species specific. When Young et. al. (1967) surveyed the plant communities, they found that two pondweed species (Potamogeton alpinus and Potamogeton x nitens) previously found in the lake were missing. This may not be significant, since they only collected from the shore so could have missed plants growing in deeper water.

The remobilisation of lead by extreme weather events

One of the worst storms to strike the Lake District in recent years was Storm Desmond in December 2015 (Marsh et al. 2016), which caused record-breaking rainfall in the Ullswater catchment and floods that damaged property in Glenridding. The effects on Glenridding Beck were spectacular, with large boulders being carried downstream by the floodwaters (Figure 6). Such disturbance is also very likely to have remobilised long-buried lead deposits (e.g. Hutchinson & Rothwell 2008), but to date, its impact on the lake remains poorly known. There is now mounting evidence that such extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and intense (Comou & Rahmstorf 2012), including in the UK (Hanlon et al. 2021).

Figure 6. Repairing the damage done by Storm Desmond to the banks of Glenridding Beck. Modified from a news feed attributed to the University of Reading.

As such, of greater concern is what might happen in the future, when warmer water in the Atlantic is projected to give rise to periods of exceptionally heavy rain caused by vapour-laden atmospheric regions dubbed ‘atmospheric rivers’ (Payne et al. 2020). The jet stream that shapes the European climate is a key influence on such ‘rivers’ (Dong et al. 2013), and the jet stream’s behaviour is becoming more erratic whilst its associated ‘storm track’ is moving south, causing more summer storms to reach the UK. Throughout post-industrial landscapes, recognising that such climatic events elevate concentrations of toxic pollutants in freshwater systems could inform strategies and actions that mitigate the ecological impacts of an unwelcome industrial legacy.

References

Comou, D. & Rahmstorf, S. 2012. A decade of weather extremes. Nature Climate Change 2: 491–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1452

Dong, B. et al. 2013. Variability in the North Atlantic summer storm track: mechanisms and impacts on European climate. Environmental Research Letters 8: 034037. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/3/034037

Hanlon, H.M. et al. 2021. Future changes to high impact weather in the UK. Climatic Change 166: 50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03100-5

Hutchinson, S.M. & Rothwell, J.J. 2008. Mobilisation of sediment-associated metals from historical Pb working sites on the River Sheaf, Sheffield, UK. Environmental Pollution 155: 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.10.033

Mackereth, F.J.H. 1965. In: Annual Report of the Freshwater Biological Association 33: 28–29.

Marsh, T. et al. 2016. The winter floods of 2015/2016 in the UK-a review. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. https://www.ceh.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2015-2016%20Winter%20Floods%20report%20Low%20Res.pdf

Payne, A.E. et al. 2020. Responses and impacts of atmospheric rivers to climate change. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1: 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0030-5

Pearsall, W.H. 1921. The development of vegetation in the English Lakes, considered in relation to the general evolution of glacial lakes and rock basins. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B 92: 259–284. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1921.0024

Welsh, R.P.H. & Denny, P. 1980. The uptake of lead and copper by submerged aquatic macrophytes in two English lakes. Journal of Ecology 68: 443–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/2259415

Young, R., Stephens, R. & Robinson, S.W. 1967. A report on flora studies and a shore reconnaissance of Lake Ullswater.

Further FBA reading

The Freshwater Biological Association publishes a wide range of books and offers a number of courses throughout the year. Check out our shop here.

Get involved

Our scientific research builds a community of action, bringing people and organisations together to deliver the urgent action needed to protect freshwaters. Join us in protecting freshwater environments now and for the future.