Understanding early life stages of the freshwater pearl mussel using scanning electron microscopy

15 December, 2025

The freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) is critically endangered, with the youngest individuals in most populations being over 80 years old because the juvenile mussels aren't surviving. Research led by Louise Lavictoire, FBA’s Head of Science, revealed why the earliest life stages are so vulnerable.

Led by scientists at the FBA and partner institutions, the research provides one of the most detailed studies to date of how juvenile freshwater pearl mussels develop after leaving their salmonid host fish.

Using scanning electron microscopy, the study examined 117 captive-reared juveniles aged between 1 and 44 months to document how their gills and feeding structures form and change over time.

Here we find out more about the research from Dr Louise Lavictoire.

Could you tell us why you did the study?

At the time, very little was known about how juvenile mussels develop as they grow, meaning we had a poor understanding of what could be driving high mortality rates during the first two months of life. Juvenile mussels are very small when they first drop off (excyst) the fish (350 – 400 µm), and so light microscopes have limited use for studying very small structures like the gills of juveniles, which I was interested in studying during my PhD.

I decided to use a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), which can achieve high magnification by using a tightly focused beam of electrons, rather than light, and electronically scanning a tiny area of the sample, allowing them to resolve much smaller details (down to nanometers) and magnify by hundreds of thousands of times.

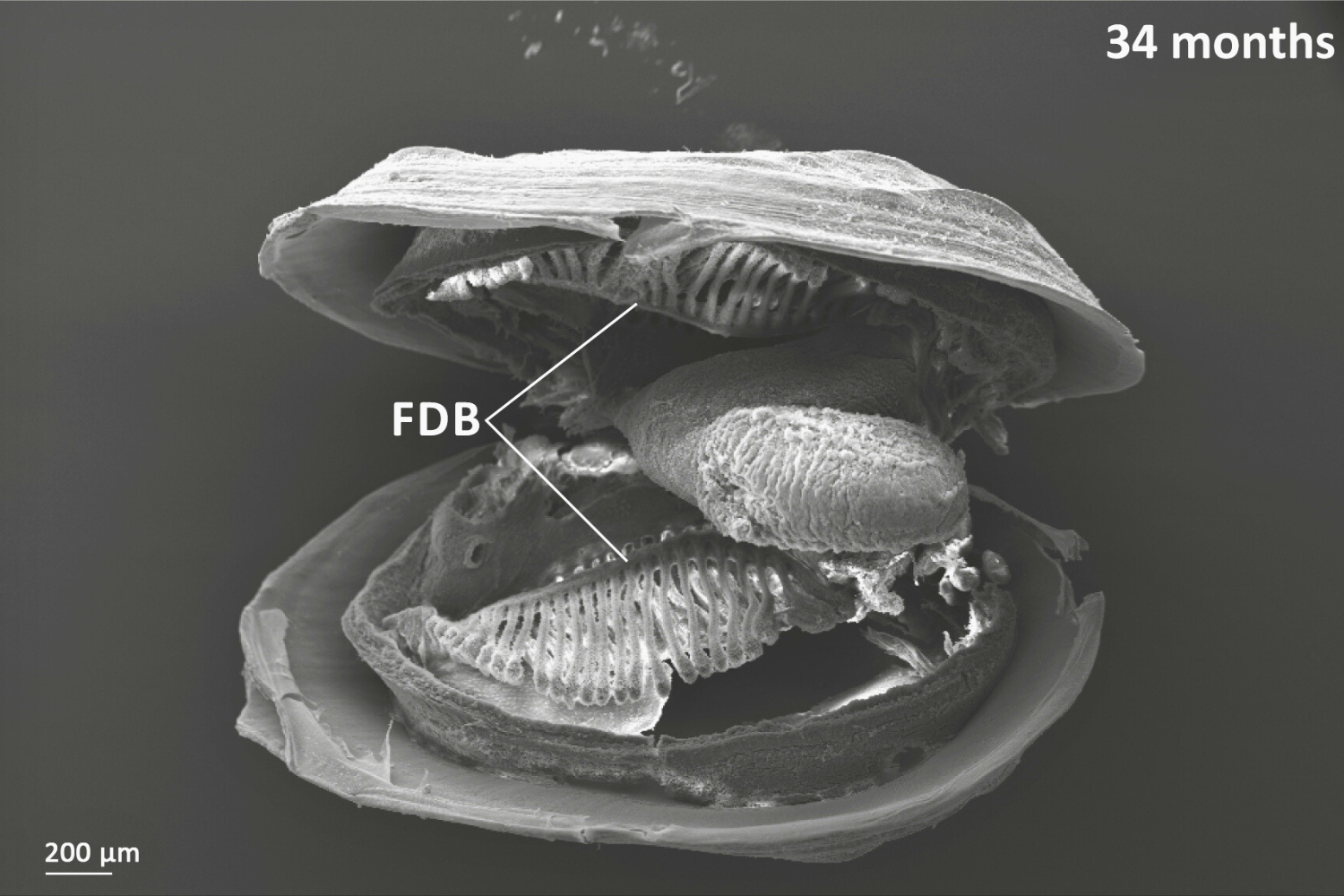

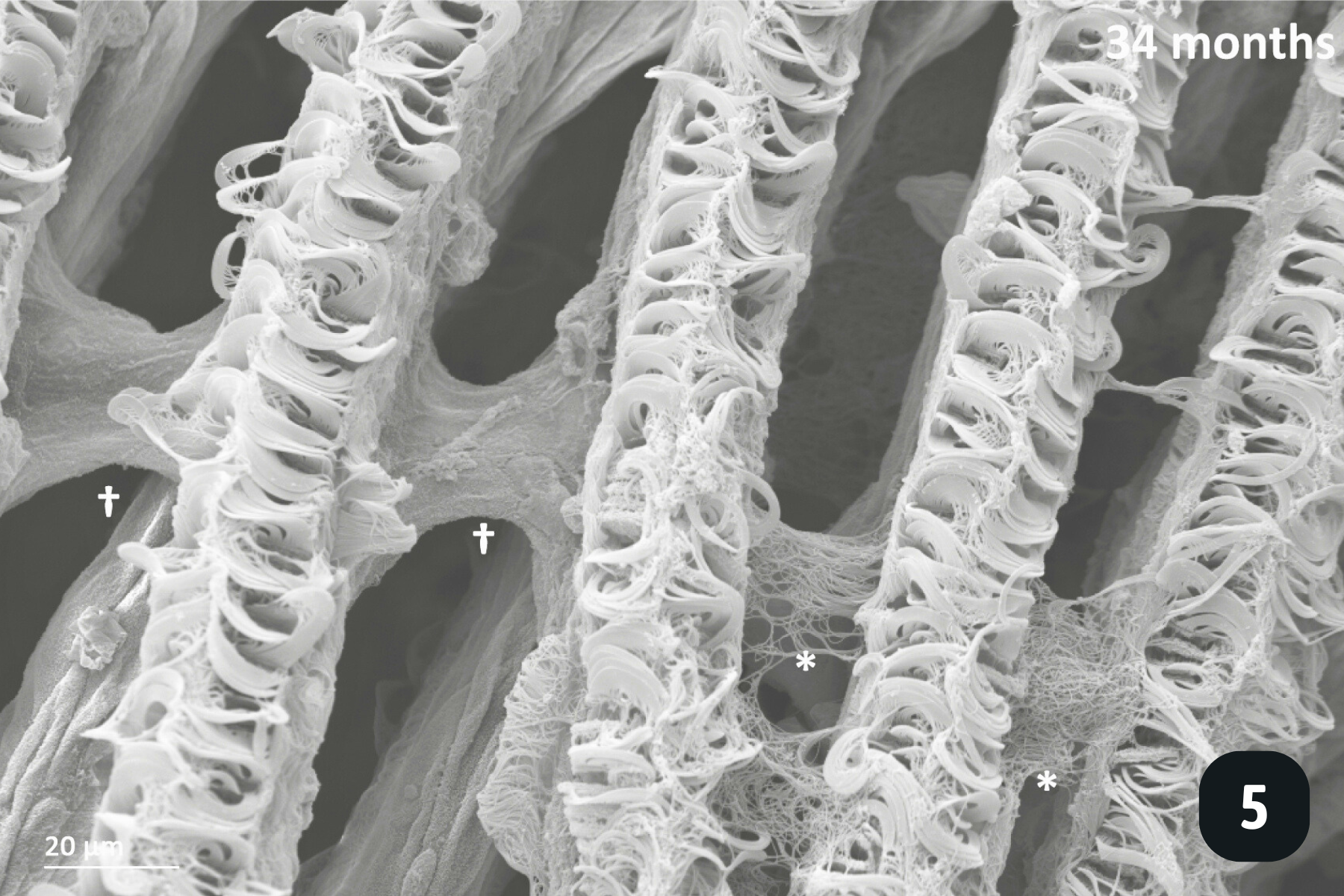

Showing a 34 month old freshwater pearl mussel. Oral groove is present on inner demibranch. Oral groove invagination is deeper in older (more anterior) filaments. On descending limb of inner demibranch: no ciliary interfilamentary junctions between filaments 1-14, cilia interfilamentary junctions between filaments 14 & 15; tissue junctions after this. No interfilamentary junctions between filaments on ascending limb. Once filament reflection has reached the budding zone then new filaments bud off already reflected (cavitation extension).

What is Scanning Electron Microscopy?

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is a technique that uses an electron beam to scan the surface of a sample, creating high-resolution images of its topography and composition. Gold coating in SEM is a process that applies a thin, conductive layer of gold onto non-conductive samples to improve image quality. This is necessary because the electron beam can cause non-conductive samples to build up an electric charge, which degrades the image. The gold coating minimizes this "charging effect", reduces beam damage, and increases conductivity, resulting in sharper and more detailed images, especially at lower to medium magnifications.

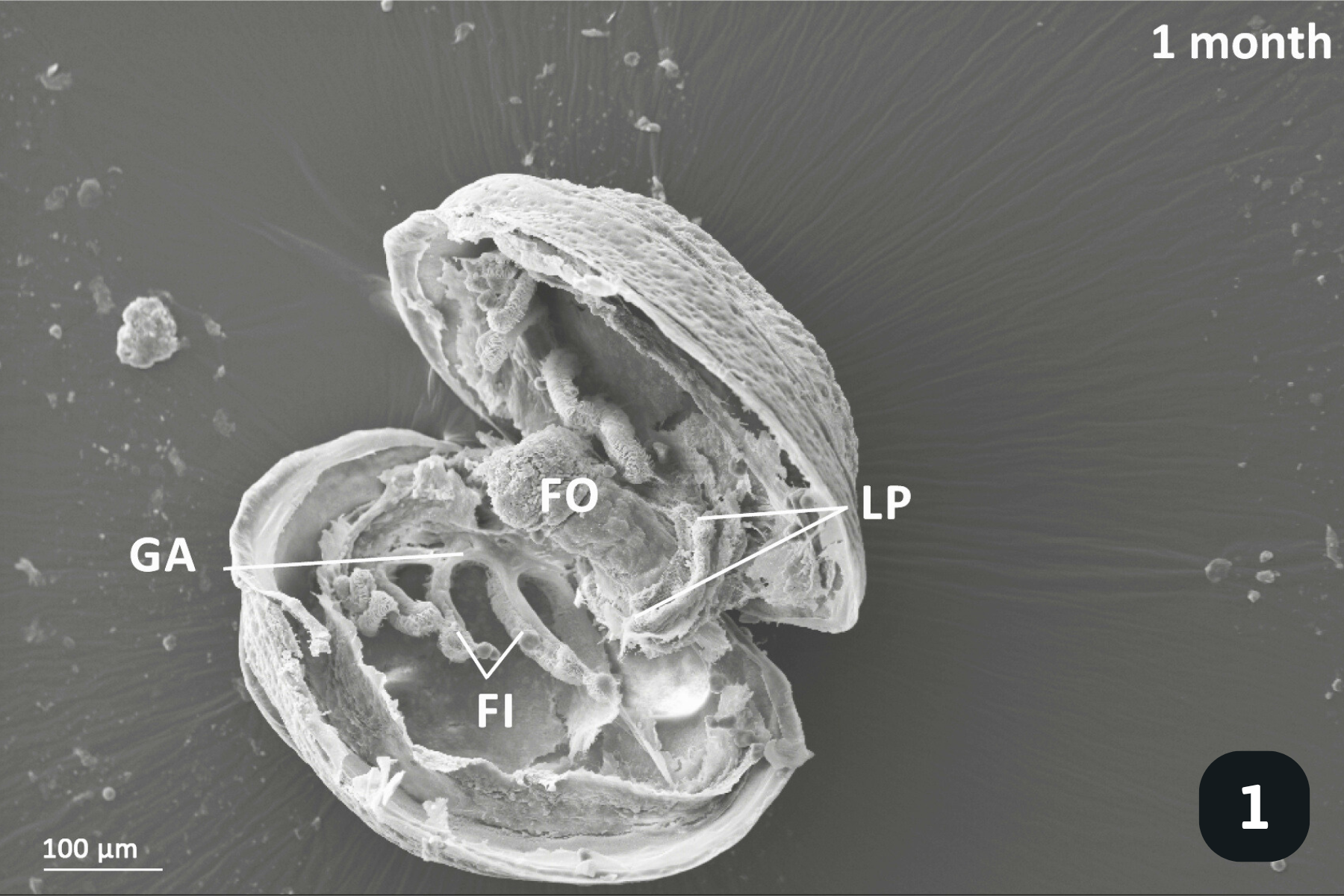

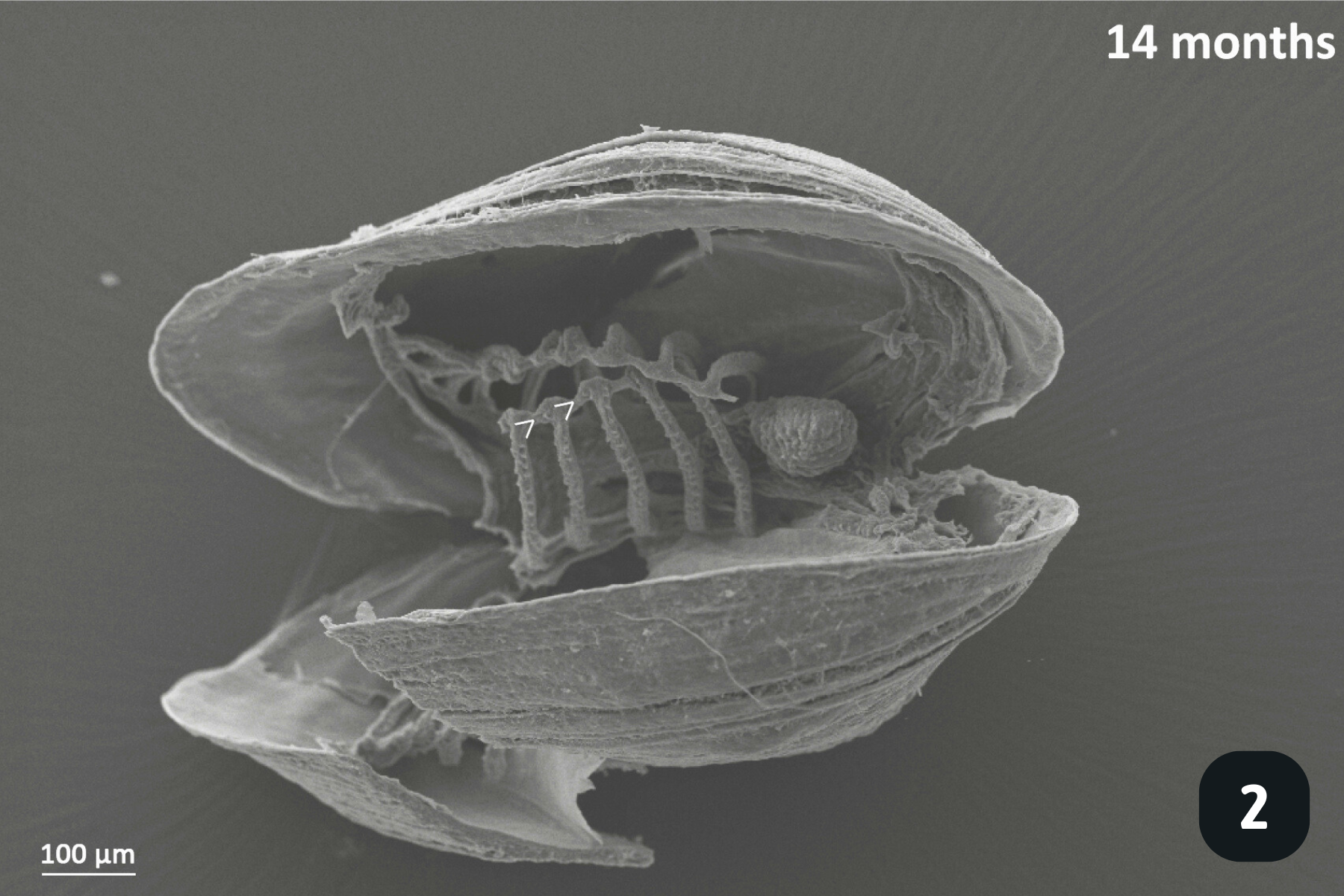

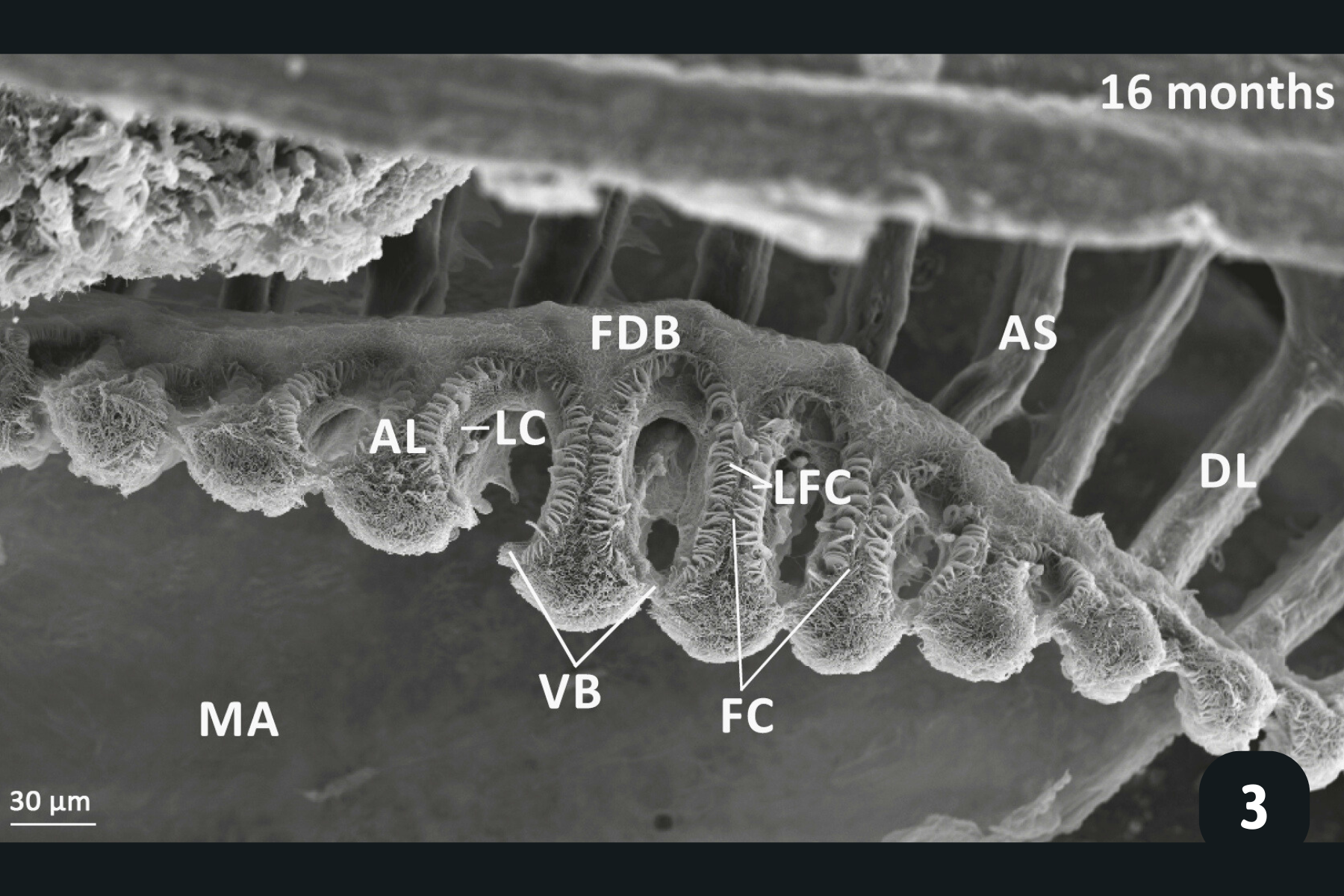

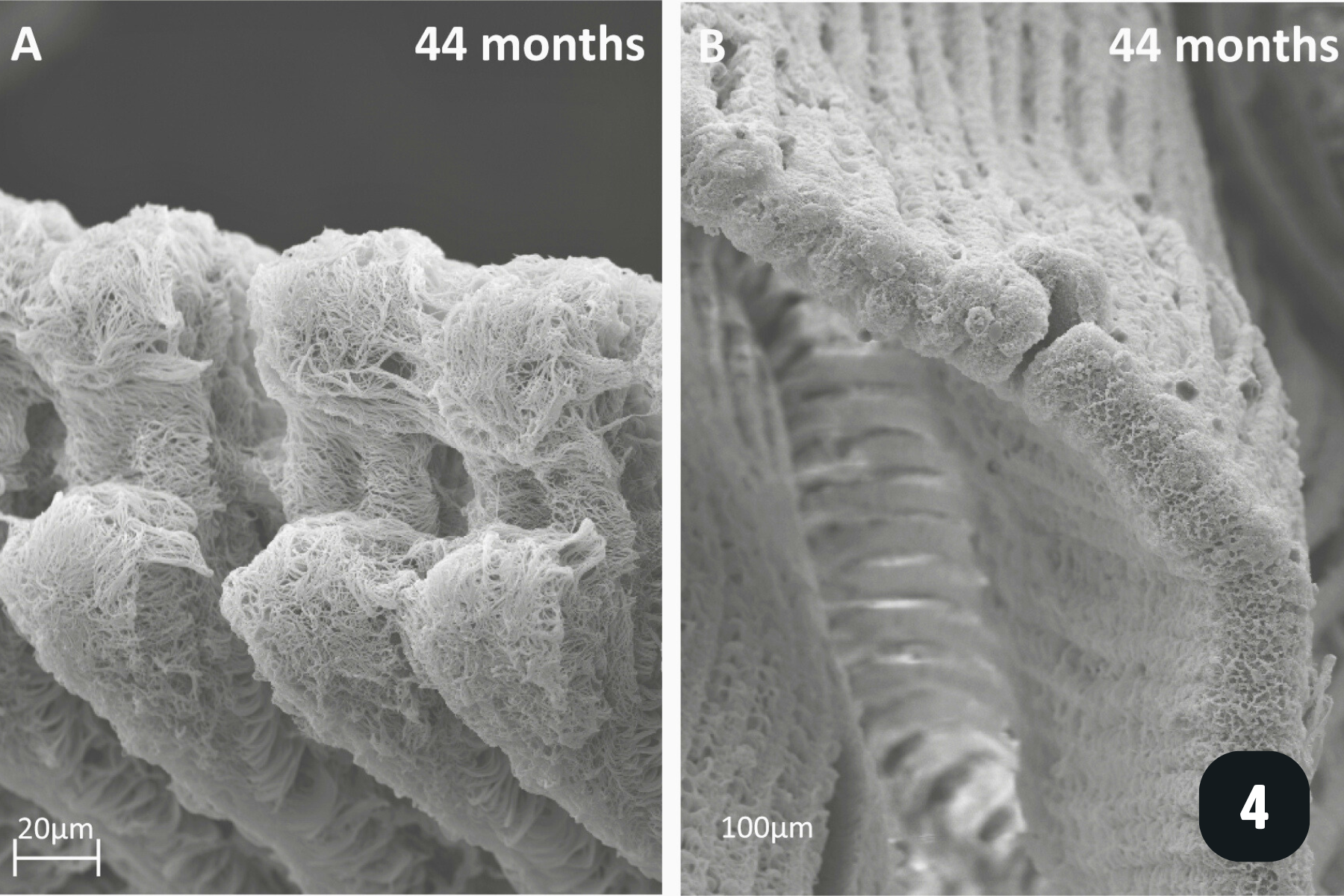

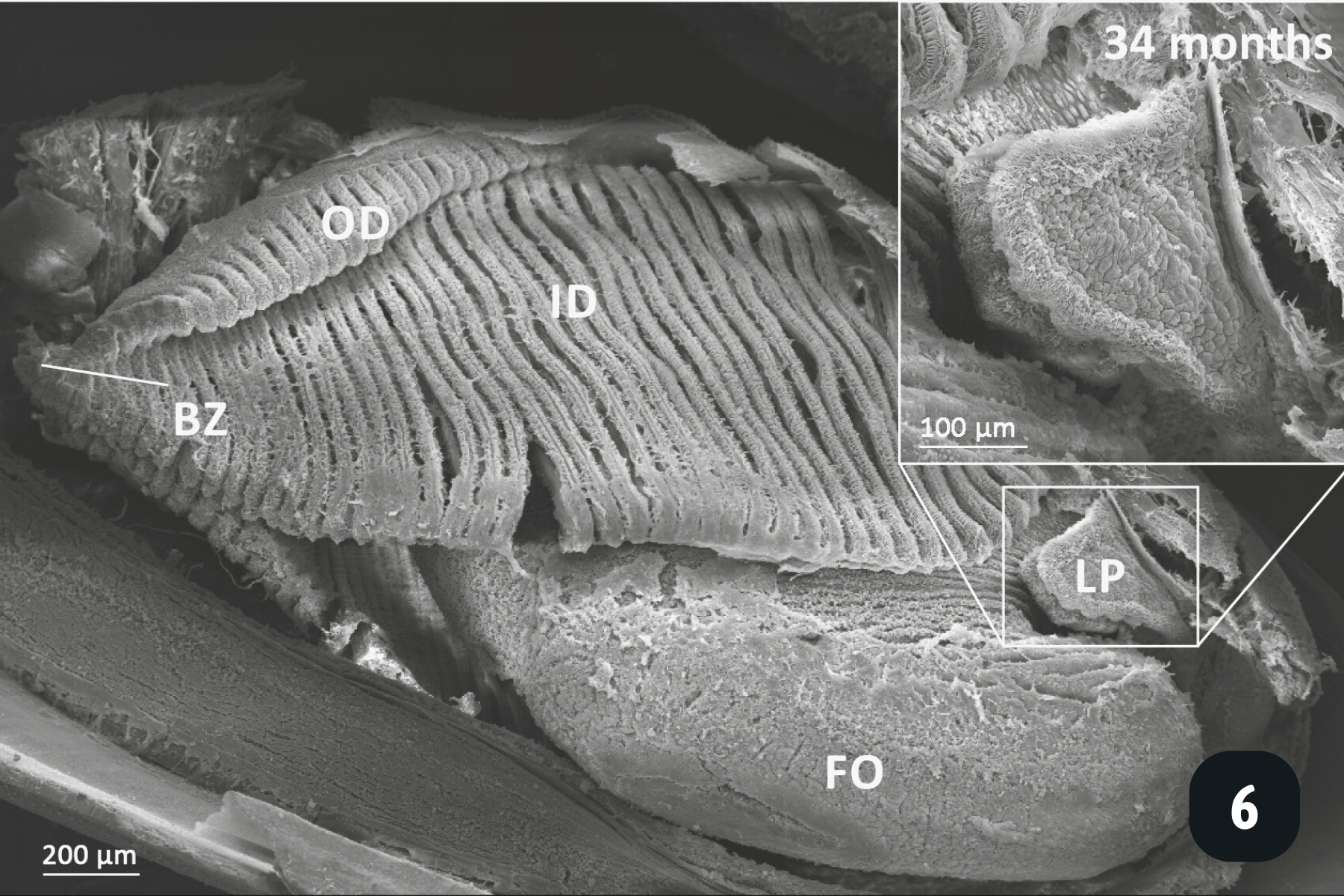

Main anatomical features of juvenile mussels. (1) Foot (FO), unreflected filaments (FI), gill axis (GA), left and right labial palps (LP). (2) Distal tips of filaments are joined to each other by thin tissue connections (arrow heads); (3) Gill reflection of the inner demibranch. Thin tissue connections join filaments at the ventral bend (VB) and the thicker fused dorsal bend (FDB) joins the terminal ends of the ascending arms. All three cilia types are present on the ascending limbs (AL); lateral cilia (LC), laterofrontal cirri (LFC) and frontal cilia (FC). The ascending limb is longer on medial filaments compared to those at either anterior or posterior ends (to the left and right of frame). Other features of note are the filament abfrontal surface (AS), descending limb (DL) and mantle (MA); (4) Oral groove on inner demibranch (left) and absence of groove on outer demibranch (right); (5) Ciliary junctions between approximately filaments 11–14 (*), after which tissue junctions were present (†); (6) Right ID, OD and labial palps (LP). Inset: Labial palps are highly ciliated on the inner surface but devoid of cilia externally.

Could you tell us what the pictures are showing?

All the pictures show various angles of the gill structures of juvenile freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera).

When juveniles first excyst the fish, they have a very rudimentary filter system to direct water, and therefore food particles, into their valves. They do this with millions of cilia (tiny hair-like structures) on their gills, mantle and foot, which beat to create water currents. The gills at this stage consist of only a few, finger-like filaments which aren’t a very powerful filter pump. Nevertheless, they pump enough water into the mantle cavity for oxygen exchange and to direct food (mainly algae) towards the mouth.

After a few months, more filaments have grown and they are starting to organise themselves by joining at the end, a precursor step to gill reflection which takes place when juveniles measure roughly 1mm in length. Gill reflection is where the joined filaments start to bend back upon themselves (see picture), to create a ‘V’ shape, rather than be a straight, finger-like structure. This is known as the inner demibranch. The gills have 3 main types of cilia:

Lateral cilia on the side of filaments – the main power-horses of water movement through the gills. Beat to direct water over the gills.

Latero-frontal cirri – more complex structures made up of tens of cilia which capture particles as the water moves past the gill filaments, and which ‘bat’ particles on to the front of the filament.

Frontal cilia – these create water currents along the frontal part of the filament, directing captured particles towards the oral groove. This is a groove at the base of the gills which directs food from all of the filaments towards the labial palps for sorting, and if the food is the right particle size, it is directed towards the mouth. If it’s the wrong particle size, it is directed towards the mantle where it is packaged up with other particles and mucus and excreted as ‘pseudo-faeces’.

As individuals grow, they develop an outer demibranch, and now have the classic ‘W’ shaped gill structure we see in adults.

This highly-sophisticated filtering mechanism can clear millions of particles from water per day depending upon the size of the mussel and the gill structures are responsible for collecting food, oxygen exchange and later in life (and if the mussel is female!), brooding glochidia. Such an amazing organ!

“This research explores perhaps my favourite chapter in my PhD which considered how the gill structures of juvenile mussels changed with size, and which ultimately improved our understanding of how their filter pump works in all its glorious complexity. Biology really is amazing!”

Why does this research matters for species recovery?

Freshwater pearl mussels can live for over a century, but survival during the first few years is extremely low. This research provides vital evidence to support species recovery and captive rearing programmes, helping conservation practitioners to:

Identify high-risk periods during juvenile development

Improve rearing conditions in conservation hatcheries

Better match food quality and particle size to juvenile feeding ability

Understand why degraded river habitats fail to support successful recruitment

By linking detailed biological development to environmental pressures, the study strengthens the scientific basis for restoring rivers and managing catchments in ways that support sustainable freshwater pearl mussel populations.

This research demonstrates the essential role of long-term, science-led recovery programmes in preventing the loss of one of the UK and Europe’s most iconic freshwater species.

By linking detailed biological development to environmental pressures, the study strengthens the scientific basis for restoring rivers and managing catchments in ways that support sustainable freshwater pearl mussel populations.

This research demonstrates the essential role of long-term, science-led recovery programmes in preventing the loss of one of the UK and Europe’s most iconic freshwater species.

Interested in discovering more?

Research report: Ontogeny of juvenile freshwater pearl mussels, Margaritifera margaritifera by Lavictoire et al. (2018), led and hosted by the Freshwater Biological Association.

Read: Avoiding extinction: Conservation breeding and population reinforcement of the freshwater pearl mussel, 20 May, 2024 By Louise Lavictoire & Chris West

Find out more about FBA's Freshwater Pearl Mussel Ark

Established in 2007, the Freshwater Pearl Mussel Recovery project is an ongoing partnership project between the Environment Agency, Natural England and the Freshwater Biological Association.