Charming the Charr

22 July, 2025

Simon Johnson introduces the exciting new LD-CHARM (Lake District Charr Recovery & Management) project.

Simon Johnson is Executive Director of the Freshwater Biological Association, based in Windermere. He is a former Director of the Wild Trout Trust and the Eden Rivers Trust, and has worked as an independent consultant for river and catchment restoration.

This article is reproduced with kind permission from the Wild Trout Trust, and first appeared in the Wild Trout Trust’s Salmo Trutta 2025.

All too often, in the world of wild native species recovery, especially cold-water fish, you’ll hear the harbingers of doom banging on that it’s “too late, not worth it, there’s no funding” etc. So, to survive and thrive, you’ll need to be radically optimistic and completely crazy. If that’s you (like me) take a high five, and read on!

This article is about a coalition of rare-fish ecologists, scientists and ‘crazies’ in the Lake District who are fighting to save one of our most special native fishes. Some may dismiss us an eclectic bunch of fish nerds, oddballs and misfits. But we’re also highly-respected molecular ecologists, geneticists, fish biologists, conservationists, creatives and anglers who are bonded by a passion for the Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus).

Being classified as a ‘post-glacial relict salmonid’ doesn’t do enough for the street cred of our Arctic charr, nor reflect the near mythical status of this beautiful native fish. In his book The Lakes of Cumberland (1786) William Gilpin offers the following vivid description:

“The Charr is most remarkable. It is near twice the size of a herring. Its back is of an olive-green: its belly of a light vermillion: softening in some parts into white; and changing into a deep red, at the insertion of the fins.”

I reckon if David Hockney ever did a fish painting, he’d portray an Arctic charr: they are truly the dandies of the fish world. And, apart from their obvious beauty, they’re also uniquely important from ecological, environmental and cultural perspectives.

Wiki Commons image. Photograph from the Freshwater and Marine Image Bank.

Arctic charr distribution

As their name implies, Arctic charr thrive in the cold waters of the sub-polar regions, and can be found across northern Europe, Russia and north America. Like their fellow salmonid the brown trout, there are sea run populations of charr (analogous to sea trout) as well as freshwater resident populations (akin to resident brown trout) – although sea run charr only occur in the northernmost part of their range; above 65 degrees latitude and not in the UK 1.

Springtime charr netting at Holbeck Point on Lake Windermere circa 1950. FBA Archives.

In England their distribution is confined to the Lake District, and they are found in many of its iconic deeper waters such as Windermere and Coniston.

Records exist of charr in other Lake District waters such as Buttermere and Crummock Water, but the paucity of monitoring on many of these lakes means that we simply don’t possess accurate data on current distribution. It is the charr of the Lake District (especially Windermere) that are the focus of this article.

Cultural importance

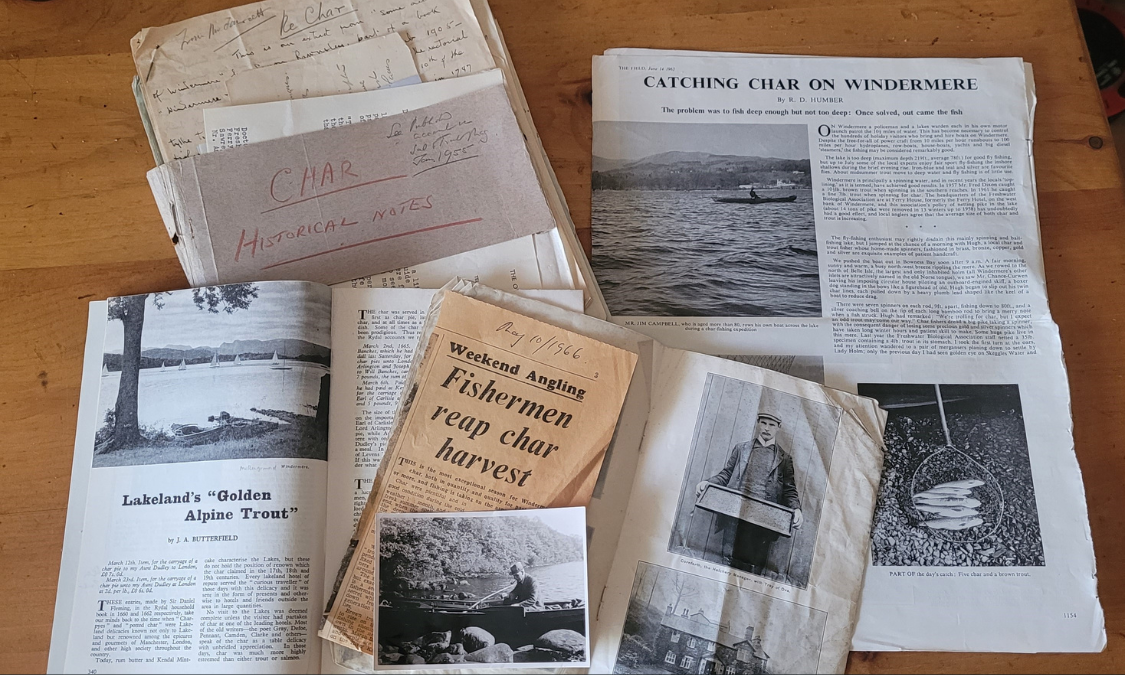

Winfield et al 2 state that as early as 1660, Arctic charr were exploited in high-profile commercial net fisheries and were greatly enjoyed by locals and in a ‘potted’ form by wealthier echelons of UK society. However, overfishing led to substantially decreased catches, and commercial netting was stopped in 1921. I’m currently delving into Winifred Frost’s personal historical archive on Windermere charr. This is a fascinating resource: for instance, she records that in 1909 Windermere & District Angling Association were running a hatchery programme for charr on the Cunsey Beck, with 230,000 ova ready for Windermere, and another 100,000 on order for Buttermere.

Historical articles and research on Arctic charr from the FBA Archive.

We also have countless magazine articles and correspondence about the recreational, scientific and commercial importance of this fishery, including how potted charr from Windermere were regularly presented to and enjoyed by royalty. I’ve also stumbled across a 20-verse song about Arctic charr fishing from just after the First World War.

Today, a few local ‘charr crazies’ persevere in fishing what might best be described as a ‘heritage approach’ using small recreational plumb-lines and artificial lures from wooden clinker boats. Sadly, many of these old charr boats ended up rotting away in the margins of once-abundant fisheries, but a great surviving example can still be seen in the Jetty Museum, Bowness-on-Windermere.

Left: Calibrating the project's hydroacoustic kit - using a toy trout and a heavy weight! Right: The author afloat on Lake Windermere.

Decline and fall

Today, Arctic charr populations in the UK are declining rapidly. Impacted by the effects of climate change, competition with invasive non-native species, habitat degradation, nutrient enrichment and likely negative genetic impacts brought about by population bottlenecks, time is running out to save this iconic species in England (Winfield et al 2008).

The Lake District of Cumbria is the sole region where Arctic charr are found in England, so it’s a critical location for conserving this species. Yet a key – and still unanswered – question is this: when did the decline of Arctic charr in Windermere start?

Catch records in our archives from renowned local charr fisher, J.B. Cooper, show some impressive results between 1965 and 1973, which might indicate that the fishery was in ‘good health’ at that time. From the start of these records to the end, average catches even increased, with hourly and daily catches of 3.64 and 27.9 fish in 1973, compared to 2.1 and 18.5 in 1965.

I’ve seen several records of 5lb+ Windermere charr in the 1940s, and the largest fish mentioned in our archive is a ‘whopper’ of 8lbs+. But over-fishing may also have played a part in the decline of charr. I’ve also seen reports from the 1960s and ‘70s stating that “10,000 fish had been ‘taken’ by just 30 anglers” and “20 boats in two days taking 1,000 fish ‘harvest’ with as many as 52 caught in a single day”.

Halcyon periods of unrestrained catch and kill on wild fisheries always end badly. It’s a guess, but in the case of Windermere I suspect that excessive fishing pressure, combined with slow environmental decline, was a disaster for our charr. Arctic charr have been identified as a priority species nationally and in the Lake District Local Nature Recovery Plan. However, as yet, little if any obvious progress has been made in conserving them.

£35,000 of multibeam imaging sonar mounted on £50 of scaffolding: what could possibly go wrong?

As readers of Ron Greer’s classic Ferox Trout and Arctic Charr 3 may recall, charr and ferox evolved together in a prey and predator relationship that is comparable to that of reindeer and wolves. In other words, if Arctic charr are threatened, so are the ferox which predate upon them: the future presence of Salmo ferox in our deep-water lakes will probably depend on the commensurate survival of Salvelinus alpinus.

Our response

Last year, the Freshwater Biological Association (FBA) called a meeting of scientists and conservationists who have a background and experience of working on Arctic charr. I don’t know what we all expected to come out of the meeting, but before long it was agreed that something needed to be done to better understand the current status and trends in charr populations, and then to use new and existing evidence to drive conservation action.

In that room was the ‘Arctic charr dream team’ of fish and molecular scientists, species recovery experts, water quality researchers, fisheries managers, ecologists, hydro-acoustic software and equipment companies and a bloke to make the tea (me!). With zero available budget, yet knowing that this issue couldn’t wait, a plan was quickly hatched to run a short trial on Windermere to assess the feasibility of using non-lethal sampling methods to detect the presence of charr during their autumn spawning season.

Arctic charr photo by Chris Conroy.

Kit, software and technical support to undertake the trial were loaned and provided by Echoview and Blueprint Subsea. The University of Hull provided eDNA sampling kit, while UKCEH provided personnel and the use of their work boat, the John Lund. FBA provided personnel and a support boat for sampling in shallow water.

£35,000 worth of state-of-the-art multi-beam hydroacoustic kit was installed on £50 worth of scaffolding frame that I ‘fabricated’ in our car park on the first morning of the trial. Before long we were loaded up and steaming towards one of the best autumn spawning sites.

Site selection and calibration was a highly technical task that involved a plastic trout being dangled off a rod and line to establish the effective beam angle and range. Kit was deployed overnight and eDNA samples were obtained before and at the end of each data run. Batteries also needed to be changed, data downloaded and eDNA samples filtered and frozen for future analysis. All this had to be fitted around the day job.

As I write this article, we’re eagerly awaiting the results of the hydro-acoustic analysis. This is a huge task involving big data files and the need for algorithms to polish the data. The eDNA samples will be analysed when we can add them onto a larger cohort of samples. Such is life when you don’t have a budget!

The one-week trial was a success in terms of testing equipment, developing our coalition and evolving our future strategy and methodologies. It was inspiring to work with such a great group of individuals who went above and beyond to support the trial.

News of our coalition and project is spreading, and we’ve just received an offer of partnership funding from the Environment Agency to support a number of initiatives, including a review of our charr archives, further eDNA work, underwater cameras, temperature loggers and organising a two-day symposium on Arctic charr science and conservation action. We’re also awaiting a decision on a major grant application via the Natural England Species Recovery Fund. If we are successful, this will turbo-charge our scientific and conservation work.

We’re very grateful to everyone who has supported us so far. The project has reminded me that we should never underestimate what a group of committed (yet crazy) folk can achieve when they come together, even without a budget!

The LD-CHARM navy: the John Lund (UKCEH) deploys with Bob the rowing boat (also UKCEH) and Winnie the dory (FBA).

What of the future?

More than ever, we need action-focused approaches like this if we hope to conserve our precious freshwater ecosystems. We need more action, less talking, and fewer failed strategies, directives, and under-funded partnerships.

Together, let’s get on with it and do good things for freshwaters with agility and pace. I’d argue that we need a paradigm shift to challenge much of the thinking and ways in which we are approaching nature recovery. In less than a lifetime, monitored freshwater populations have fallen by an average of 83%, the largest decline of any species group 4. Time is really against us, and this is why our Arctic charr recovery project, and many others like it, really can’t wait.

John Quincy Adams, 6th President of the USA, once said: “If our actions right now inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more and become more, then we have fulfilled our obligations as leaders.”

I’ll leave you to ponder on that…

Post-publication update on support for LD-CHARM

We are delighted to announce that, since publication of this WTT article, the Lake District Arctic Charr Recovery and Management project has been awarded £128,000 through Natural England’s Species Recovery Programme to support vital research to help save Arctic charr populations in England from extinction.

The LD-CHARM project aligns with Natural England's commitment to reversing species decline and promoting biodiversity across England. Through collaborative efforts and dedicated research, the LD-CHARM project aims to ensure the long-term survival of Arctic charr in the Lake District, preserving this unique species for future generations.

Read the full news article here: Huge funding boost from Natural England for threatened fish in the Lake District

The LD-CHARM Coalition

The Lake District - Charr Recovery & Management (LD-CHARM) project is a consortium led by the Freshwater Biological Association involving the following partners: Echoview (active hydroacoustic data & software specialists); Blueprint Subsea (manufacturers of hydroacoustic hardware); UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (lake ecology and eDNA expertise); Colin Bean - Honorary Professor at University of Glasgow; University of Highlands & Islands (population genetics); Institute of Fisheries Management (knowledge exchange); Lake District National Park Authority (nature recovery); Westmorland & Furness Council (owner of bed of Windermere); Environment Agency (North West); Natural England (the government's adviser for the natural environment in England).

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the Wild Trout Trust for allowing the reproduction of this article on the FBA website.

References

1. Adapted from Williams, Dr Phill (2002) Post-Glacial Relict Salmonids: Arctic Charr, Ferox Trout and Whitefish

2. Winfield, Ian J; Berry, Richard; Iddon, Henry (2019) The cultural importance and international recognition of the Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus populations of Windermere, UK (in special issue: Charr biology, ecology and management) Hydrobiologia, 840 (1)

3. Greer, Ron (1995) Ferox Trout and Arctic Charr: A Predator, its Pursuit and its Prey

4. World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?804991/84-collapse-in-Freshwater-species-populations-since-1970

Further FBA reading

Find out more about the Lake District - Arctic Charr Recovery & Management project.

The Freshwater Biological Association publishes a wide range of books and offers a number of courses throughout the year. Check out our shop here.

Get involved

Our scientific research builds a community of action, bringing people and organisations together to deliver the urgent action needed to protect freshwaters. Join us in protecting freshwater environments now and for the future.